03 March 2020 by Helena Uhde, ECECP Junior Postgraduate Fellow

It was not just recently, that researchers, think tanks and decision makers started warning about the wasted investment into coal power plants. There is a political consensus in the EU and in China, that a shift towards a low-carbon economy is necessary. Leading financial institutions are increasingly backing out of coal investments and reports show that the existing coal mines are sufficient to cover demand. According to an analysis by Carbon Tracker (2015), projects with a total value of USD 2 trillion globally are in risk to become stranded assets. And in policy workshops and articles, terms like “stranded assets”, “overcapacity crisis”, “coal bubble” and “just transition” are repeated constantly. But what does this mean and how did we get here?

It was not just recently, that researchers, think tanks and decision makers started warning about the wasted investment into coal power plants. There is a political consensus in the EU and in China, that a shift towards a low-carbon economy is necessary. Leading financial institutions are increasingly backing out of coal investments and reports show that the existing coal mines are sufficient to cover demand. According to an analysis by Carbon Tracker (2015), projects with a total value of USD 2 trillion globally are in risk to become stranded assets. And in policy workshops and articles, terms like “stranded assets”, “overcapacity crisis”, “coal bubble” and “just transition” are repeated constantly. But what does this mean and how did we get here?

Stranded assets

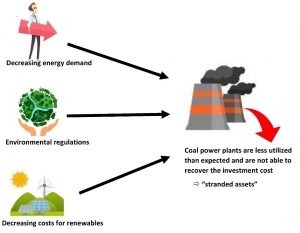

The term “stranded assets” is used to describe investment projects that are unable to recover their investment cost, and therefore leading to a loss for investors. In the energy context, we mainly talk about coal power plants which are not operated as intended due to climate policies and decreasing costs for renewable energy. If the international community wants to comply with the targets set in the Paris Agreement, a large part of the coal resources used for value estimations cannot be monetized, leading to a “coal bubble”.

Drivers for this development are a slowing demand growth, environmental policies and the decreasing cost for renewables, which make coal power less competitive.

Figure 1 Drivers for coal transitions. Source of icons: Freepik.com.

The situation in China and the EU

China determined to reach its carbon peak by 2030 and the “battle against pollution” is one of the three major challenges mentioned during the 19th National Congress of the party. The mitigation of overcapacity in the coal sector is an important step towards cleaner energy supply. Reserve margins, as an indicator for over capacity, reached more than 70% in Gansu, Heilongjiang, Shanxi, Liaoning, Jilin and Inner Mongolia in 2015. Particularly the small coal power plants with a capacity below 300,000 t/a tend to use backward technologies and not complying to the industry policies and regulations (Fei, 2018). In order to cut at least 25% of overcapacity, China started to merge state-owned coal power assets in Gansu, Shaanxi, the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region, Qinghai, and the Ningxia Hui autonomous region.

In December the European Commission presented the European Green Deal, which aims to make Europe a climate-neutral continent by 2050. If the EU takes its 2°C target seriously, it will have to deal with an estimated 85GW of stranded asset capacity, which sums up to about EUR 50 billion in investment losses. Especially regions that depend on economic monostructures, such as the North of Great Britain, the South of Italy, large parts of Eastern Europe and Eastern Germany are vulnerable.

Reducing the risks

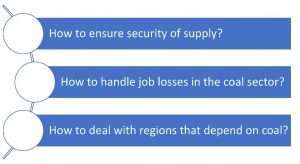

There are two types of risks that need to be addressed with adequate policies: coal power plants as stranded assets and mining regions. If stranded assets are not addressed properly, they might affect social stability and have a negative impact in the international efforts against climate change. In mining regions, governments face three challenges: security of supply, loss of jobs in the coal sector, and the regions economically affected by the transition.

How can we reduce the future risk of stranded assets in the coal sector? The first step for governments is to provide investors and other stakeholders with more transparent information on the risk of investments into fossil fuels with the background of climate policies. By creating a standard practice for climate-related reporting, investors and other stakeholders can be protected. On the decision-makers side, more rigorous project planning and approval are necessary to avoid further overcapacities. The emissions trading systems (ETS) in the EU and China are important instruments for internalizing the environmental costs of coal-fired power generation. In the long run, market mechanisms help to signal the real value of assets, so that further investment into loss making coal power plants is avoided.

Figure 2 Main challenges for jurisdictions in face of a coal phase-out.

In order to ensure the security of supply, coal power needs to be replaced by a portfolio of renewable energy and flexibility mechanisms. Fitting coal power plants with Carbon capture and storage (CCS) or Carbon capture utilization and storage (CCUS) technology could expand the lifetime of coal power plants. Due to the high costs of the technology development, forecasts expect though, that even with CCS and CCUS, coal power plants will only remain as a minor part in the energy mix.

Structural policies to tackle unemployment and empower vulnerable regions

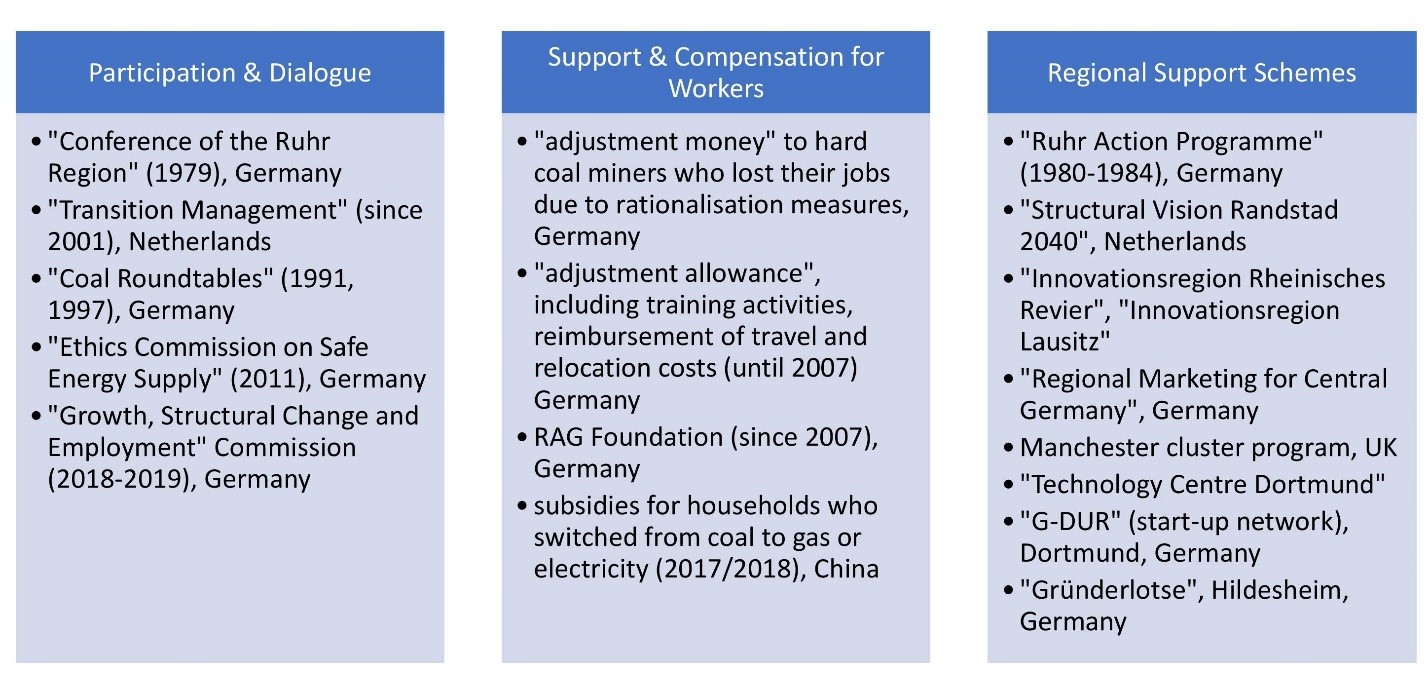

Drawing on experiences from the past, three elements of structural policies have been proven successful to tackle unemployment and empower vulnerable regions: 1) Participation and dialogue forums, 2) Support and compensation schemes for workers in affected sectors and 3) Regional support schemes to promote economic diversification and reorientation. Table 1 shows a collection of examples for the different support schemes.

Table 1 Examples of structural policies for coal transitions. Concept based on Schulz and Schwartzkopff (2016).

In order to get to a political consensus for the implementation of structural policies, open discussions with different stakeholder groups are useful to collect ideas and to make an informed decision on how money is spent. A recent example in the EU is the ‘Growth, Structural Change and Employment’ Commission appointed by the German Federal Government, which worked from 2018 to 2019 to formulate measures to reach the 2030 emissions target and to develop a policy mix for affected regions. Stakeholder discussions are also important in the residential sector in China, where especially lower income households rely on coal to meet their energy needs.

Support and compensation for workers, including remunerations for those who lost their jobs and funds for trainings are a common policy tool. In China, after a policy that required three million households to switch from coal to gas or electricity for heating, cooking and hot water supply was implemented in August 2017 by the Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP), subsidies to compensate these households for higher energy costs and the installation of new equipment was provided. Drawing on experience from coal phase outs in the German energy sector, the authors in a recent report suggest not only to offer compensations for younger employees in the coal industry, but also to address innovations and economic potential of all sectors in a specific region.

Figure 3 Structural policies for coal transitions. Source of icons: Freepik.com.

Regional support schemes are important to help a region to restructure its economic potential. Structural development measures include investments in the economy, science, infrastructure and soft-location factors. The promotion of soft-location factors, such as standards of living and attractiveness of a location, are needed to keep workers in the region, so that companies investing into the region find the skilled personal they need. Measures to support soft-location factors are investments into cultural and leisure activities, childcare and other services for young families. With its initiative “Coal regions in transition”, the EU aims to establish transition strategies for regions that rely on coal and to identify and implement innovative solutions. And in China, the government can rely on extensive experience from its cluster policy in e.g. technology and innovation parks. Since each region has its own specificities, participation and stakeholder dialogue should always be the first step in finding tailor-made solutions and using resources most effectively.

Exchange between the EU and China can foster new ideas

Both in the EU and China, under-utilization of coal fired power plants brings great challenges, such as energy substitution, finding other sources of employment and economic challenges for coal dependent regions. In order to avoid further investment losses, the construction of new coal power plants needs to be re-evaluated, and stopped if a stranded asset is foreseeable. Transparency measures, such as the creation of reporting guidelines, can help to inform investors about the risk of their investments. Stakeholder dialogues, compensations for workers and regional support schemes can help to absorb the negative effects. And finally, an intensive exchange between the EU and China about new ideas for regional support schemes and lessons learned from the process can bring benefits for both sides.

A shortened version of this article has published in the ECECP newsletter, which can be found here as a PDF.

Helena is an ECECP Junior Research Fellow and is currently a PhD candidate at the Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research at Beijing Institute of Technology (CEEP-BIT). Contact Helena